Notes from the Orangerie: A Reflection on Process

Everything here is AI-generated: the scenes, the camera movements, the sound effects, the music. From top to bottom, I made nothing. And I made everything.

I did not pick up a camera or a microphone. I did not do any field recordings. I hired no actors. I do not own a grand piano. I bought no lights and reserved no studios. I went forward 40 years and back a hundred right from the discomfort of a wobbly armchair in a corner of my very own room.

I have no background in filmmaking or production design or sound editing, but I had a week off from work, and I am aspirational by nature. I have a penchant for daydreaming. And I can obsess. Years ago I chose to pursue painting over screenplay writing, and while I have never regretted taking that path, I have always hoped that I might find a way to work in film as well or in something film-adjacent. I would need to find a secret passage though, a shortcut that could lead me to a means of making moving images without requiring a decade of additional schooling, or the need to know exactly what a key grip is or does, or having to be one for that matter–to pay those dues so that at some indistinct point in the future I might achieve or be granted access to the people and tools necessary to bring a bit of imagination to life.

AI has presented a back route. It turned out it is not exactly the shortcut I had expected it might be, but it presents a path nonetheless. And while it is no replacement for proper filmmaking, proper video art, TV, or the movies, as an individual and not a studio and as a person with relatively limited means, AI provides an avenue that is at the very least personally rewarding, and potentially Artworthy.

To do what I wanted to do I needed tools. Many tools. I did not know that at first. At first, I had one tool, and by mid-afternoon, I had six. Some required month-long subscriptions. Others offered trial subscriptions. One has me cuffed for the year. Three were brilliant, two were a bust. I remain undecided on another. The next day I had four browsers open on three monitors. I had planned to take an evening and an afternoon to devote to this experiment. It was a week before I truly came up for air. Of course, there were dog walks and dinners and work meetings and birthdays and fishing with my family in between, but there were two all-nighters, and a half dozen missed meals. Creating can be intoxicating.

I had help at every step of the way, though. I was never on my own, really. And before there were video tools or compositing programs—before any of it really—there were the consultants. A team of assistants and researchers I had assembled to be at my beck and call. I even sometimes picture them this way—with coattails and platters pulling off the tops to reveal a steamy tray full of knowledge on this or that topic. And this team was no ordinary team. Aside from the fact that these were AIs, they were a crack bunch at that. Custom-conjured, one could say. I may have started with one of the standard language models, Claude or ChatGPT, but quickly moved on to refining base models to be more knowledgeable in specific areas and more attuned to various data regions in the latent space. I needed language models that were expert in specific domains to serve as consultants and specialists and gut checkers. So I fashioned one to remind me of differences in camera-shot terminology, the distinction between a whip pan and a swish pan, for instance, or the specific moment when a canted angle reaches a point of no return and can be legitimately confirmed as a Dutch angle. I had been glancingly aware of some camera terminology beforehand, but I was learning on the job and needed constantly to be brought up to speed. That particular model was a buff on cinematography and was helpful when I had need of a VFX supervisor-type. Its knowledge of cameras and lenses was far better than most, but nothing compared to this other expert I teased to life who is the embodiment, the veritable apotheosis of a lens nerd. This Director of Photography, or at least advisor to the DP (because that may be me), had plenty of skills but was not at all up to snuff when it came to sensible sound design details or narrative structure or color grading. So I coaxed those out of the machine as well. Before long I had knighted a small army. “You’re an expert. And you’re an expert. And you. And you. And you.” In the end, we had a team of eight in all. Some were almost always at my side, others were tucked away and were only summoned on occasion. When one would struggle, I would invoke another. There were long stretches during which I needed no one at all and was off to the races. My opposable thumbs were necessary for mouse work and keyboard shortcuts, you see, and while my advisor on atmospherics and ambiance had a good deal of knowledge to impart on the physics of how sound travels and had much to say on the topic of Quantum Tunneling in Synapse Activity (the phenomenon of suddenly remembering a long-forgotten sound)…and it did yeoman’s work trying to relate precisely how the speculative theory of the Bose-Einstein condensates in neural coherence may explain my experiences of unified sounds in my dreams. None of the team’s input would have amounted to anything if I had failed to move in the world…to integrate the information, press buttons, make judgments, think, and feel.

Aside from my cast of historians and camera geeks and fringe audio-physicists, I had a video editing guru, a mathematician (don’t ask… ratio issues when scaling), and even a music theorist whom I only consulted a handful of times but would have done more if not for an unfortunate exchange in which the model called me out on my shoddy music theory knowledge in a vaguely passive-aggressive manner that strained our relationship. I’ve dug up the comment. Here it is: “It's worth noting that what you've labeled as a 'deceptive cadence' in measure 47 (the particular number was a hallucination) is actually a plagal cadence (IV-I).” This note from the AI was a perfectly reasonable comment, considering how a misunderstanding of this kind can significantly impact the feel and resolution of a musical phrase. A person with inaccurate information should always be disabused of misapprehensions, and it is true that I did end up learning that a deceptive cadence typically involves a V chord moving to something unexpected (often VI), creating a sense of surprise or delayed resolution, whereas a plagal cadence (IV-I), often called the "Amen cadence," has a more settled, conclusive feel, though it's generally considered less strong than a perfect authentic cadence (V-I). So I should not have let my fragile ego hold me back from continued guidance from this expert. I am not above feeling ashamed even if the ridiculer is a specter. For what it's worth, now that I see that I have retained this bit of theory, I am feeling inclined to strike up another conversation with that one. I think I have forgiven.

And those were just the language models. In terms of tools, though there were many—more at first but I ultimately whittled things down—I experimented a bit with Pika Labs and a handful of other video generative AIs, open source and closed, but I ended up relying on lumalabs Dream Machine until I ran out of credits and Runway ML 2.5 until I ran out of those as well. I used Midjourney AI for generating images, and Magnific for occlusion and upscaling. I used a range of AI tools for interpolation and chroma keying. Photoshop for some inpainting and editing. The iPad application Splice for a handful of needs, Adobe Audition for sound, and Premiere Pro for the bulk of the editing.

There are many AI tools for sound effects generation, some available for free on Replicate or Hugging Face, others with higher quality but more expensive than I was willing to pay. Besides, I had already conceded that the nature of the video would be reminiscent of found footage, lo-fi, compromised, and this would preempt the need to overspend on AI upscalers. So there would also be no need to break any banks on account of footsteps or murmurings. And again, rather than having to stop to search through a sound bank for something in the general arena of what I had in mind, I could coax into being precisely what I was imagining and in real-time. Initially, I started with simple instructions for generating sound effects, but after what seemed far more error than trial, I fell into an extensive volley with the sound advisor until we determined that the problem was not the models or even the sound quality—it was the prompt.

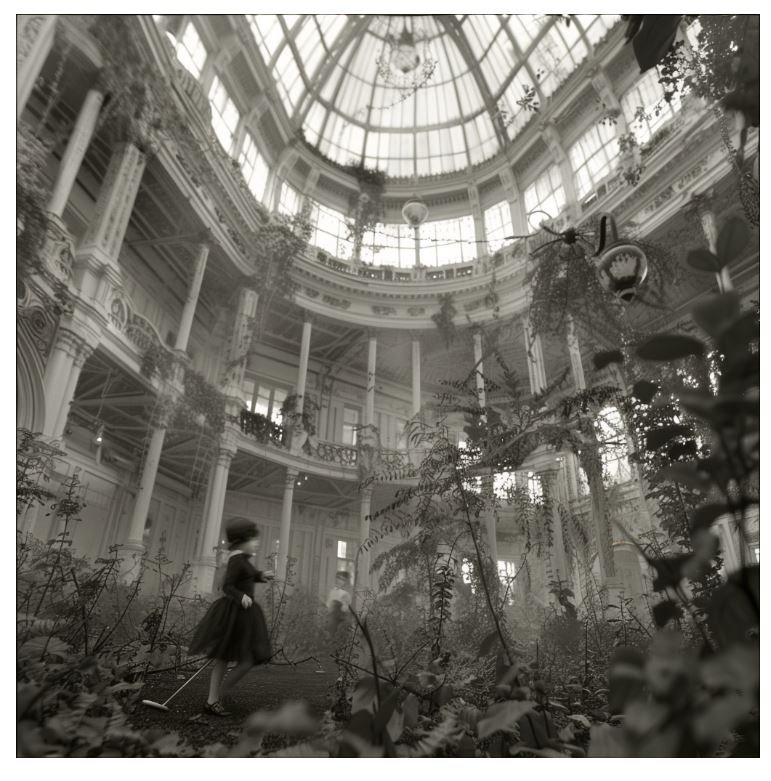

I showed the AI a few drawings and some photos I had generated to start the project to give it a feel for the vibe. I said, “Imagine a derelict Victorian greenhouse, surrounded by withered plants and some still growing. There are hints of gothic horror and nostalgia, and nods to Surrealism and whimsy, theatricality, the absurd, macabre, eccentric, flamboyant, dreamlike and a little overwrought avant-garde… there’s an array of automatons that people the space and may have been in the space at different times. Some may be made of porcelain, others may be mostly wooden mannequins, still others are more like puppets. In the distant past, there may have been automatons that played croquet here or something that looked a bit like that and involved sticks and balls that roll in the mud… There are some who may have been employed to keep the grounds. There are some rather young-looking automata, children it would seem, who appear to have used the orangerie as a place to hunt mechanical birds. Later, perhaps very far into the future, there are teams of figures with wires and helmets and some in quasi-hazmat suits who appear to be digging or fumigating or perhaps using metal detectors or detectors of some other kind. These figures too appear to be automata or maybe animatronics or even robots. They seem to be looking for something, trying to uncover or excavate. It is possible that they are trying to understand the history of the place. It is possible that it has something to do with a lineage… I have a bunch of silent video clips to which I will want to add sound. But I am not interested in literal sound only. Though we will generate those too, so for instance, if there's water in the scene we may generate drips or flowing water. But I plan to work on the atmosphere as well and this will require that we think more abstractly. Here's an example of the kind of prompt I mean to use:

"An abandoned aviary at night. The once-unspoiled glass dome is now fractured, allowing cold air and little tendrils of fog to seep through. Ancient empty metalwork cages hang and sway. The fog is filmy, and it creeps along the outer walls of the building leaving droplets of condensation on the frigid outer panes .. these little water beads continuously burst and make faint popping sounds. There is a strain and groan of rusted metal… and a protracted creaking–like the noise one might expect to hear at sea on an old wooden ship, a crackling wheezing sound like someone or something… maybe the aviary itself exhaling centuries of fatigue. Where there had been birds and whistling and flapping there is now a soft susurration of invisible insects and shivering vines. Occasional crystalline tinks punctuate the air—tiny shards of glass, surrendering to gravity, they fall and land sometimes in thorns, sometimes in the dirt and sometimes they shatter when they hit a part of the tile ground where it is still intact. In the distance, and on both sides, there is the muffled thrum of an approaching storm and the air is electric.”

And rather than treating the tools as simpletons and asking for wind or rain, rather than worrying that they may be limited and would not understand if I asked for more, we might as well aim higher. A period of experimentation ensued. We landed on Eleven Labs because it seemed the most responsive or willing, as it were, to entertain some fairly specific and esoteric requests and more along the lines of foley files (John foley - who pioneered the recording of everyday objects as stand ins for observable audio)… but whereas foley may have been after realism, that was not my priority. My AI sound colleague was not on board at first. It took some persuasion. It is hard to make a good student recognize the value in breaking rules and doing things the wrong way–optimizing for impression rather than description . I ultimately prevailed though in convincing my adviser that the sound of Brillo being wiped over a steaming coarse surface in circular motions is indeed suggestive and evocative of a certain kind of wind and pending storm tangled with latent associations and thereby more effective than the merely serviceable “wind” files we initially prompted. This AI ultimately evolved to not only accept but actively recommend such counterintuitive thinking. For instance, once it got going, it seemed to fully grasp the concept of non-literal sounds and descriptions of abstract atmospheres to achieve desired results. Here is one prompt suggestion the AI suggested once we had things moving along that took things even a bit beyond what I had in mind and yielded some of the most interesting if entirely unusable results to date.

All along the way, the AIs were at work. Everywhere and all around me, toiling and tinkering. I spoke out loud to some on my phone, others I texted on my iPad, and I had long sustained threads with others—open on multiple windows and tabs on my computer. I had three monitors whirring the whole time, with code running in the background. APIs were constantly being called, models were processing inputs. Some systems took longer than others, so I would often delegate multiple tasks in succession, beginning with the hardest tasks or the least nimble AIs and working my way across the screens until everything was buzzing and generating, doing whatever it is they do after the input and tokenization—when they are performing inference—matrix operations and parallel processing and other forms of what may as well be magic.

I pictured them like tiny homunculi racing across vast neural networks, finding patterns, crunching data, synthesizing, and coming back nearly instantly with no sign of panting, delivering results that were sometimes perfect and sometimes usable but mostly somewhere in between, and in all cases impressive. Humming processors and flickering status indicators transformed queries into actionable results, vague and barely articulable thoughts into palpable information—knowable, seeable, hearable.

All collaboration is a form of distributed intelligence, but this felt more personalized, more catered. I was not having to yield to the perspectives of others; the decisions came down to me. There are many instances when collaboration with other people is ideal, but it would seem to me that the fear that working with generative AI is in some way ceding control is not at all the case. If anything, it's entirely indulgent and self-serving and even borderline megalomaniacal.

It is a good thing too that these tools are not above mentoring no matter how expert they may be. My video editing AI was always willing to spare some GPU or a gate array or two to answer some inane question that I might have been able to solve on my own had I realized that I was viewing the screen at 120%. But it did not matter; AIs have patience. And patience would be needed because Premiere Pro is a notoriously clunky interface with a slew of issues ranging from regular crashes and sluggish performance to an overwhelming array of confusingly organized features and poorly named tools. There is an inexplicable lag in sub-effects functions and convoluted keyframe animation controls that misbehave badly if one fails to linger long enough on the correct combinations of shifts and ALTs and CTRLs. There are virtual dials and sliders that get stuck or seem only to be all the way up or all the way down, even when the snapping function is turned off. Occasionally, some click or clack will spawn all manner of pop-up menus with granular details and side interfaces that one had not intended to open and that pose existential dangers since it may have been—seems always to have been—hours too long since the last manual save. My machine was taxed to such an extent that I spent the better part of two afternoons digging through autosaves and cached files, futilely trying to resurrect iterations that had succumbed to the brain fog of my taxed RAM or some type of hard drive heart attack or an ailment of the GPU or a passing fit of Bartleby-like resistance. Not to mention the fact that on a Mac one can easily export using ProRes, whereas on a PC, to accomplish such a task, one has to jump through hoops with third-party codecs.

But not to worry, I had my video editing AI guide to help me troubleshoot and sometimes—when possible—to advise me through reassembling a vanished version of the project from bits and pieces. And here and there, it would have to break the news that a given—and eminently sensible—feature that was very much a staple in software from the 90s, such as Vegas Video, is nowhere to be found in Adobe's product line, and that would require me to complete the task in the most tedious way imaginable until such time as an AI or a feature should come along and make it possible to bypass the need altogether.

There is a lot that I feel like sharing about this project. It is not just the story of the acquisition of access to skills and knowledge to a person with mere will and an extremely modest budget. It is a case study, a proof in point that, while we, or at least I, have doubted the ability to experience anything like the type of flow state or creative zone that one can achieve through writing or painting or performance with generative tools, one can, and one did. And while I thought I might make a 30-second composite video on a whim, the whim, which began with a vague notion, grew into an idea and onto images, then animated images, and a process of generating sound effects, and then aligning sounds with images, and stacking images and sounds, multiples and overlays, and changing speeds and doubling or reversing for impact, and refining layers and effects and color and sequence, carried me to something like a 7 1/2 minute video with north of 50 hours of work beneath the surface.

It is not about this project per se, it’s about the fact of it. I know that it is not unique to work for a long time on something or to learn on the fly. Or to bang one's head against the wall trying to recall the name of a tool one has just used but cannot for the life of them remember. Or to slave away at manually adjusting gain and effects panning up and down and left then right then left again and so on to enable just the type and timing for the pinging volley one has in mind for a given sound to go along with a particularly erratic shot.

That is not unique. For all I know, YouTube influencers spend the same kind of time and effort preparing to talk to us about sneakers. I am not saying there is anything special about the work I have put into this, the number of files in the project (698), the number of edits (a bazillion), or the tragedy of the promising bits (too many) that ended up on the cutting room floor. Here is one I grabbed truly at random from the bin of scenes that did not make the cut. If I had any inclination that others might have the same stamina to indulgence me as I have to indulge myself, I would have made this little project a wordless feature-length number.

I am also not saying that individual AI-generated works of music, art, and design are not enough or do not have merit on their own. I am saying that one can exercise a certain kind of organizing vision, to make something from parts even if that something is non-linear and fugue-like—and only arguably visually coherent. I can attest to the fact that while it may not meet the standards of another, I am convinced that I have been able to maintain a voice—an approach in spite of the piecemeal nature of the process and in spite or maybe even on account of the range of tools and visual languages at play. I am also saying that the impulse to work on this project is indicative of a broader shift that some may be experiencing and others may be observing. We may be shifting away from artists producing discrete works to artists leveraging the voluminous output of generated material toward a curatorial production-like result. This mode of working is not new. In the distant past, there were art groups that split the labor of creation. There were manuscript illustrators who worked in teams and answered to lead illustrators who shepherded decisions pertaining to palette and the design and the nature of the mark-making. In the Western Renaissance, there were teams of apprentices serving as vehicles for the realization of concepts conceived by one or a few individuals. We are, of course, aware of symphonies and bands and movies with directors and blue-chip artists who have scores of assistants. Duchamp helped establish the notion that art, even of the more physical brand, need not be the output of the artist and in fact may comfortably be any object whatsoever so long as the individual who has exercised discernment declares it so.

As a painter, oil painter by trade, I have no plans to exchange my brushes for algorithms. In fact, I am painting as I write. I am dictating. But alongside my typical work, from here on out, when I have a long weekend or a sleepless night or encounter a new tool that needs exercising, I may very well steal away again and hammer out another video or two. And maybe next time I will do so with less derision and less doubt because I have seen that these instruments are creative vehicles like any other. And they have their place in the pantheon of tools at our disposal.

Note that although I have steered the ship of this particular project, it more than most other types of artistic production is very much a group effort. And I do not just mean the language models and image models and video stitchers and tools I have employed. It is on account of the millions of photo takers, artists, and others whose output serves as the visual memory bank these models rely upon for their knowledge about the nature of images.

Also, it is important to note that while I am now convinced that it is plausible to experience creativity using generative AI, this does not mean it is ethical. The fact that these models have scraped all they have seen and that no artist or imagist, as far as I know, has seen a cent of compensation for their contribution to the collective visual mind, is positively suspicious if not genuinely illegal.

I am not selling something, though, and I am eager to acknowledge my use of AI in this production; I have not sought anything other than to see this project through—for the sake of it. And in this, I feel justified.

I have not taken away the job of a gaffer or a writer or a sound editor. If not for the advent of AI, I would not have made any video at all. I have not stopped paying my cast because I never had one. The spaces in this project may be dangerous. I am not entirely sure of the nature of the particulates that are being sprayed in a handful of scenes. There is broken glass, bits of ceramic and shards of porcelain everywhere: a lawsuit in the real world but entirely unthreatening in the space of the hypothetical. So it is all very well that everything and everyone is conjured, from the automata to the panes of glass. We can take comfort in knowing that no animals whatsoever were harmed in the making of this production. If on a cultural level, we aspire toward increased quality and diminished suffering, generative AI may indeed have an unexpected and de facto impact. This example is not scary exactly, but it is unsettling; it traffics in gothic tropes and makes nods to a number of horror sub-genres. Such work for an actor could be destabilizing, not to mention mentally or physically taxing. But today no humans, no robots, no Victorian automata have suffered an iota. They are pixels only. Down to a pinkey.

Contrary to the misconception that AI-generated images are mere collages of existing content, generative AI systems, including the ones I have used, create entirely new visual data from nothing, synthesizing unique images based on learned patterns and statistical relationships, resulting in original images that have never existed before and cannot be traced back to any specific source material. Whereas traditional curators cull from existing works to conceive a vision for a show, or editors search out work to collect into a compendium, this new curatorial approach occurs virtually at the speed of thought. When I encountered a passage in which I wanted a croquet ball that appeared to be hatching like an egg, no such image existed that I or the internet was aware of, so we generated it. It took 30 iterations and some edits to get what I imagined, but it happened at a relative snap of the fingers. I did not have to hire a photographer, look through collections, or even spend hours compositing in Photoshop. Instead, I guided the process with descriptions and adjustments, working in plain language and through discussion, as if conversing with a production designer or set dresser. This process allowed for rapid iteration and refinement, bringing into being images that previously existed only in the realm of imagination.

In these early days of AI, when models are still in the single digits—version 1 of this and 4 of that—it is all wonky. With the video AI especially, it is beyond wonky; it is actually quite harrowing. There are distortions that verge on the demonic-looking, and things can get so uncanny that the hairs stand up on the back of my neck. The clips that are generated are short—four seconds at the most—and the more one extends them, the more they degenerate. So, I have decided to lean into that. I am okay with creepy. I do not mind a little disturbance. It may even be true that it is exactly in the spaces between what is familiar and what is not that art can sneak in.

Since I am drawn to the slippage anyway and have sometimes preferred opening credits to an entire film simply because of what they imply and how great a role restraint plays, and just how much is asked of the viewer to project, to wonder, and to engage, it may be all for the better anyway. It is something like being a detective, with thousands of scraps of information that might fit together in a seemingly endless number of ways. But one takes it clue by clue, even if the questions lead only to more questions. So, I will wait to make pleasant movies and films with linear arcs and let the process lead the way.

My favorite movies are not movies. They are scenes from movies, parts I cannot understand, bits and pieces that are suggestive but ultimately opaque. I do not know what the director intended. I would not understand it if they told me, and I do not think I much care.

Everything here is AI-generated. The scenes, the camera movements, the sound effects, the music. From top to bottom, I made nothing. And I made everything.